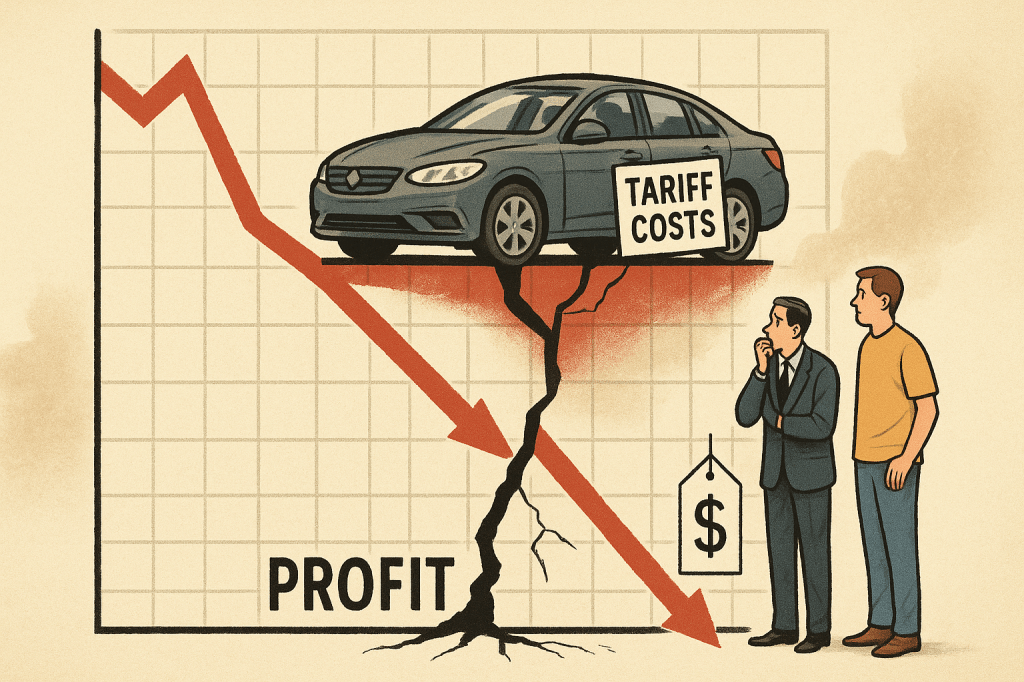

Automakers are facing billions in tariff costs on imported steel, aluminum, and car parts. Yet, surprisingly, car prices have remained relatively steady. In this lesson, learners will explore how global trade policy, corporate strategy, and economic pressures interact. Using an NPR report as a foundation, this lesson is ideal for advanced English learners interested in current events, global economics, and public policy.

| Automakers are eating the cost of tariffs — for now |

Warm-up question: Have you or someone you know recently bought a car? Was it expensive? Why do you think car prices are rising or staying high?

Listen: Link to audio [HERE]

Read:

JUANA SUMMERS, HOST:

Tariffs on imported goods have hit the auto industry hard. But if you’ve been shopping for a new car recently, you might have noticed that prices – well, I mean, they’re still high, but they’re not much higher than before the tariffs hit. NPR’s Camila Domonoske takes a look at why.

CAMILA DOMONOSKE, BYLINE: The auto industry is a truly global industry, with parts crisscrossing the world. So tariffs on steel, aluminum, car parts and imported cars, which have all been in place since this spring, they’re taking a bite. Trade deals have been lowering some of those tariffs and might lower more, but they are still significant taxes. Take Stellantis, which makes Chrysler, Dodge, Jeep and Ram. Yesterday, CFO Doug Ostermann gave investors a rundown on the tariff numbers.

DOUG OSTERMANN: And they’re big, right? We talked about the full tariff impact for the year. Right now, our estimate is 1.5 billion.

DOMONOSKE: Just last quarter, GM paid 1.1 billion. Hyundai and Kia together paid more than a billion. Volkswagen, 1.5 billion. But the prices that car buyers pay? They barely went up.

ERIN KEATING: Yeah, it’s been a little bit surprising, but good for the consumer.

DOMONOSKE: That’s Erin Keating, executive analyst for Cox Automotive, the company that owns Kelley Blue Book. As for why…

KEATING: For a majority of the automakers, they’re really taking the tariffs on the chin.

DOMONOSKE: For now, companies are mostly not passing those costs along. Ivan Drury is with the auto data company Edmunds.

IVAN DRURY: Some have said, look, we know we cannot increase prices. You know, consumers are already stretched thin.

DOMONOSKE: The average new car is almost $50,000. Even used cars now average nearly 30K. A record number of people are paying more than $1,000 a month on their car payment. Growing numbers are underwater on their loans, owing more than their cars are worth. At some point, cars simply cost too much. So Drury says, for companies…

DRURY: You know, really, price is almost the last thing they’re touching when it comes to, how are we going to, like, deal with these tariffs?

DOMONOSKE: The first thing they’re doing is taking it from profits, but Wall Street doesn’t want them to do that forever. What are the other options? Well, companies can move some production to the U.S. They can cut their costs, which might mean squeezing smaller companies that supply to them or just finding savings to offset the tariffs. But while car prices might be the last thing automakers touch, Drury says they’ll get there, eventually.

DRURY: I actually think that a lot of consumers will notice that when it comes to the 2026 model year vehicles, which are coming onto lots in the next few months, that’s where you might see a bit of bump in price.

DOMONOSKE: It’s easier to stomach a price hike when it comes with a new model year, maybe some new features. Keating, with Cox Automotive, agrees, expecting the new model year to come with price hikes.

KEATING: We’ve done some calculations. We anticipate that pricing would rise 4 to 8%, 8% really being the max before truly a car is going to price itself out of its competitive set.

DOMONOSKE: No carmaker wants to be the first to raise prices, but once someone does, they probably all will.

Camila Domonoske, NPR News.

Vocabulary and Phrases:

| Word / Phrase | Meaning | Korean Translation |

| Crisscrossing | Moving back and forth across an area in many directions. | 이리저리 교차하며 움직이는 것 |

| Take a bite | To have a noticeable negative effect; to reduce something (like profit or income). | (이익이나 소득 등을) 갉아먹다, 줄이다 |

| Take on the chin | To accept a difficult or painful situation without complaining. | 묵묵히 받아들이다, 감수하다 |

| Stretched thin | Being under pressure because of having too many demands and not enough resources or energy. | 너무 많은 일을 떠맡아 여유가 없는 상태 |

| Underwater on a loan | Owing more money on a loan than the value of the thing purchased (e.g., car, house). | 대출금이 자산 가치보다 더 많은 상태 |

| Squeeze | To apply pressure, especially to get more money or effort from someone. | 압박하다, 쥐어짜다 |

| Stomach (verb) | To be able to accept or deal with something unpleasant. | 견디다, 참다 |

Comprehension Questions:

- Why haven’t car prices gone up significantly, even though automakers are paying large amounts in tariffs?

- What does it mean when Keating says companies are “taking the tariffs on the chin”?

- What evidence does the report give that consumers are “stretched thin”?

- What are some of the ways automakers are dealing with the cost of tariffs besides raising prices?

- Why might automakers choose to raise prices when the 2026 models are released?

- How does Wall Street influence how long companies can avoid raising prices?

- What risk do car companies face if they raise prices too much?

Discussion Questions:

- Do you think companies should pass extra costs (like tariffs) to consumers, or try to absorb them? Why?

- Have you or someone you know ever been “stretched thin” financially? What helped in that situation?

- How do global economic decisions (like tariffs) affect people in your country?

- If car prices go up again soon, what changes might you expect in consumer behavior?

- What would you do if you were “underwater” on a car or home loan?